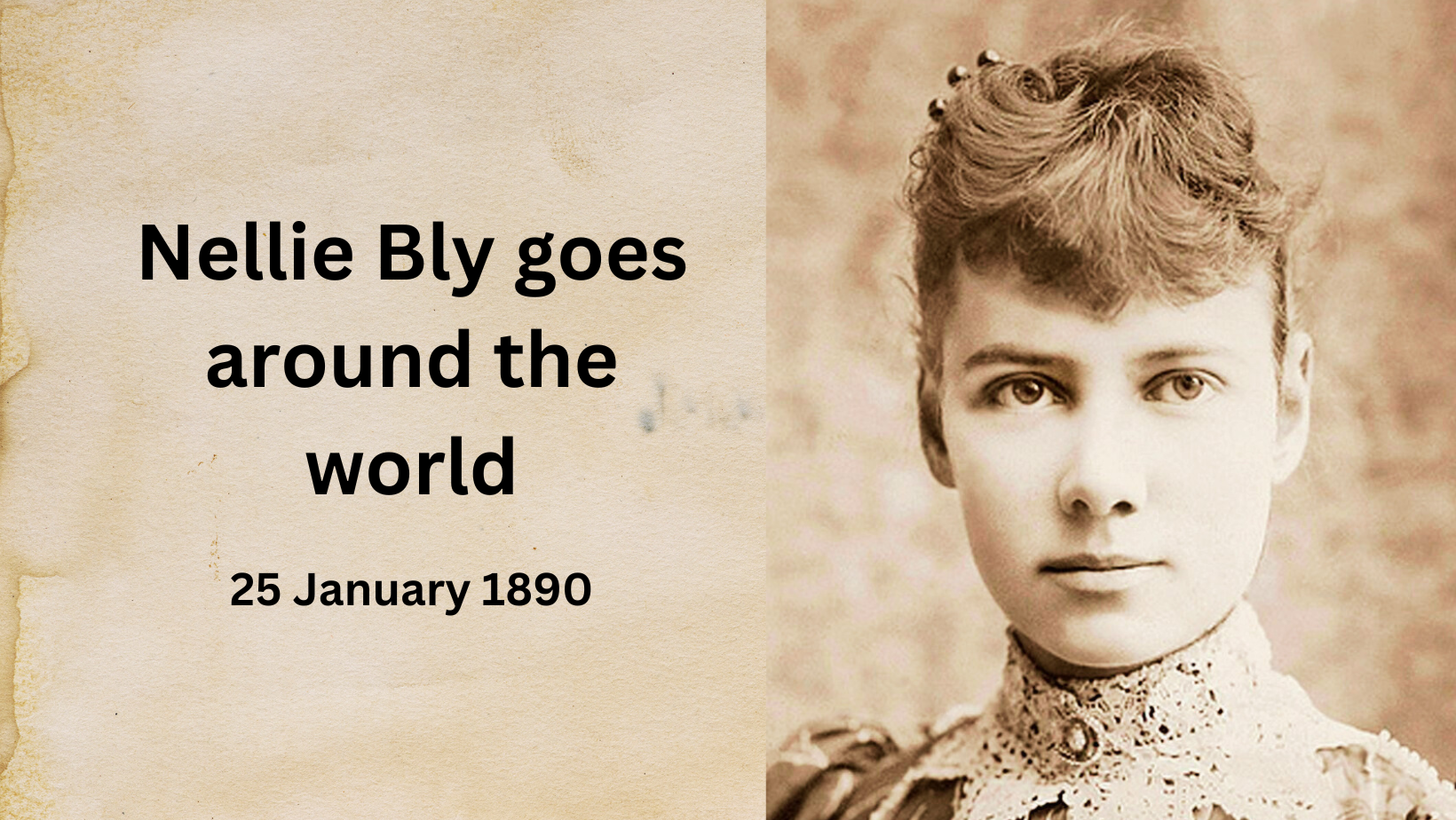

On 25 January 1890, American journalist Nellie Bly stepped off a train in New York and into a huge crowd that was waiting for her. She had just become the first person to travel around the world in less than eighty days. Not only had she done it, she had beaten her rival, Elizabeth Bisland, by four days.

The 1890 race around the world reveals that Bly, perhaps the most famous newswoman then writing, was not unique. From 1887 through to the middle of the 1890s, the ‘stunt girls’ made front page news. They wrote it, and they became it.

So in this post we’re looking at the rise and fall of stunt journalism, and the women involved in it.

Reporting on social injustice

Undercover reporting was not new. It was a form of campaign journalism that aimed to highlight unjust situations through first hand observation. Some men had gone undercover to report from the South before the US Civil War. Augustus St Clair, writing as Helen C Weeks, ran a sting campaign against illegal abortionists (there being no other kind) in the New York Times in 1871. Helen Stuart Campbell wrote a series called ‘Prisoners of Poverty’ for the New York Tribune in 1886-1887.1 Mostly, though, women who wanted to be journalists were confined to soft news such as the latest fashions, the arts or who’d been to a marvellous party.

“The city newsroom was still considered too manly, too coarse, and too unladylike. Women, it was argued, were “temperamentally unsuited to work in newsrooms, where the pace was like lightning, and men smoked, drank, and swore.” “2

Journalism was changing in the late nineteenth century, as technology made it cheaper and literacy levels rose. Between 1870 and 1899, the number of daily newspapers in the US quadrupled.3 And, as we all know today, more outlets mean a demand for more content, and the more sensational the better. Two newspaper proprietors, Carnegie and Hearst, dove straight in to the sensationalism.

Enter Nellie Bly and Carnegie’s New York World. Bly, eager to secure a job in the newsroom approached the editor in 1887 with an idea for an undercover story. She would travel to England then return in steerage, disguised as a poor immigrant. The editor didn’t love the idea. Instead he suggested Bly go undercover in the city, and get herself committed to the Blackwell Insane Asylum for poor women. She agreed. The first story in her series, told with apparent girlish enthusiasm for her mission, was published on 9 October 1887. By the time the second story came out, Bly’s name was in the headline and on the front page. Overnight, the sub-genre of “stunt girl” journalism was born. These women were “not just reporting the news but becoming the news”. 4

For the first five years or so, the so-called stunt girls were chronicling and exposing working class urban life.

“They offered themselves as mediators between their readers the city, deliberately embracing situations in which the female body was likely to be viewed as suspect, oversexed, out of control.” 5

One academic studying the 1890s British undercover journalist T Sparrow suggests the tone and style of stunt girl reporting is a late flourish of the Gothic. The stunt girl writing provided “pleasure by allowing readers to experience danger and discomfort vicariously and from a comfortable distance.” 6

The first half of the stunt girl reporting does, though, lead to changes. The budget for the asylum Bly had been sent to was increased by 57 percent within a year. A corrupt elected official leaves town. A doctor is struck off. San Francisco improves its emergency care after Annie Laurie exposed her mistreatment. The women in one of the garment factories Eva Gay had worked in go on strike for better conditions. Gay, responding to criticism of her methods said “Let them treat their employees fairly and justly, there will then be no work for me to do.”7

“In the 1880s and 1890s, male writers would produce their share of undercover work, largely among the unemployed, but in that period, women predominated in stealth reporting on workplace hardship and abuse.”8

Stunt reporting loses its way

In 1880, there were 288 women working as reporters or editors in US press. By 1890, it was 600. 9

As the turn of the century approached the stunts become more important than anything they might be exposing. The stunts become the news. Kim Todd puts it well. They were “less in disguise, less really overtly in the public interest and more … driving trains, climbing bridges.”10. By 1896, Bly, who had once exposed the horrors behind the locked doors of an asylum was clearly tired of her editor’s ideas about stunts.

“I tried to train an elephant last week. The elephant was scared. So was I. Neither of us mentioned it at the time. But I have thought of it since and doubtless so has he.”11

Other women investigative journalists sought to distance themselves from the stunt girls. If they were white it was because they thought it was cheap sensationalism. If they were Black, like Ida B Wells, because they were busy “documenting horrors, not recounting adventures”.12

“African American newswomen did more than avoid the stunt reporting genre: they wrote against its central premise. The drama of endangered whiteness that served as a critical subtext for white newswomen’s “stunts” also fuelled narratives that justified the lynchings of black men.” 13

Going undercover still happened after the heyday of American stunt girls in the 1880s-1890s. Gloria Steinem went undercover as a Playboy Bunny in 1963, the stunt element coming from a vocal feminist exploring a male fantasy of women being empowered through…er, wearing a bunny suit.14 Other modern undercover stories are more brutal, less amusing and closer to the original social plight reportage. In 2004 Sandra Ochoa was recruited by Ginger Thompson to report on the experience of being in the hands of people smugglers.15

One final note: two of the ‘stunt girls’ ended up reporting from Europe during World War One. Clearly some of them never gave up their willingness to take risks for the story.

Nellie Bly and the original “stunt girl” reporters

So who were the women who leapt at this opportunity to escape the society pages, even if it meant leaping into a diving cassion that might give them the bends? Here’s some of their names, in the order in which they started doing stunt reporting.

Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, writing as Nellie Bly (1864-1922)

Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

Bly set the whole genre in train with her Ten Days in the Mad-House series for the New York World in 1887. She trailed around the dispensaries in New York to report on malpractice, very nearly losing part of a tonsil in her quest for the story. She interviewed anarchist Emma Goldman. And, of course, she raced around the world. Her reporting made her a celebrity. There was even a board game.

Bly eventually left journalism (perhaps the elephant assignment was the last straw), got married to a businessman, nearly lost everything. She wound up in Austria in 1914, was mistaken for a British spy, and ended up reporting from the Serbian/Austrian front line.

Helen Cusach, writing as Nell Nelson (1865?-1945)

Nelson went undercover at a cigarette factory in 1888 for the Chicago Times. Whilst there she was subjected to the classic “here, let me show you” sexual assault move by a male supervisor.

A girl reporter (unknown dates)

A still unknown woman was part of a series, also in the Chicago Times, who posed as a desperate pregnant woman in order to write an expose of abortionists. She was attacked in the pages of the Journal of the American Medical Association for “sneaking around like a snake” and destroying the reputation of some of the doctors who offered her the procedure.

Her identity has never been uncovered. Given the careful balance ‘stunt girls’ walked to maintain their respectability, “pretending to be pregnant out of wedlock and seeking an abortion may have been over the line of what a reporter might do and emerge unscathed.” 16

Eliza Putnam Heaton (1860-1919)

Heaton wrote under her own name, unlike most ‘stunt girls’. Unlike Bly, she was able to convince an editor to let her go undercover in steerage class from England to New York in 1888. She went on establish a daily news page focussed on women’s movements such as the suffragists, and to be one of the founders of the Women’s Press club.

Eleanor Stackhouse Atkinson, writing as Nora Marks (1863-1942)

For two years from 1888, Nora reported for the Chicago Tribune, going undercover as a housemaid, a stockyard worker and more. She then dropped out of the journalism business and wrote the children’s book Greyfriars Bobby. Perhaps she’d done enough first-hand reporting at the Tribune, as she did not visit Edinburgh before writing the book. Her daughter, Dorothy Blake, wrote a novel about a girl reporter in Chicago.

Eva McDonald Valesh, writing as Eva Gay (1866-1956)

Valesh got an old dress out of the ragbag so she could go undercover in the garment factories of St Paul in 1888. She was an active campaigner for labour rights, seeking to improve women’s working conditions. The women in the first factory she reported on went on strike to demand better terms and conditions.

She moved to New York after factory owners in St Paul got wise to how she looked and took a job with Hearst’s New York Journal. In 1898 she was sent by Hearst to cover the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. Over time, her activism diminished until, by the shirtwaist strike of 1910 she was attaching the unions as too socialist.

Winifred Sweet Black, writing as Annie Laurie (1863-1936)

Black got a doctor friend of hers to put belladonna drops in her eyes, then feigned a collapse in the street in 1890. Her report on how she was treated caused San Francisco to set up its first ambulance service. As with Valesh, the organisations Black was reporting on started to look out for her – not helped by her distinctive red hair.

In 1900, a category four hurricane hit Galveston, killing around 8,000 people. A military cordon was set up around the ruined city. Black disguised herself as a boy and talked her way through the cordon. Her tactic meant she was the first reporter on the scene. She went on to report on the San Francisco earthquake and from Europe during World War One.

Black always denied she was a ‘stunt’ girl, despite employing their tactics.

Elizabeth Banks, writing as An American Girl (1865-1938)

Banks couldn’t catch a break as a ‘stunt girl’ in the US, so in 1893 she headed to London where she went undercover as a housemaid, a street sweeper etc. Her reporting was seen as breaching the rules of English journalism, not least because she named the households she worked for.

Ada Patterson (1867-1931)

Patterson was apparently looking for a newsroom break in 1897 when she heard the New York American was looking for a woman to do a report urgently. She showed up and was asked if she would be willing to risk the bends by going down in a cassion of the East River bridge. She agreed, went down, filed her report and was hired. The only fly in the ointment was the New York World had also sent a ‘stunt girl’ down: Meg Merrilies’ report was published on the same day as Patterson’s.

Meg Merrilies (dates unknown)

Merrilies was a catch-all penname for a whole heap of ‘stunt girl’ reporters at the New York World. The publishers had launched Bly’s career, and then realised they had made her name. Her celebrity was a problem, so Merrilies was invented to stop the other stunt girls they employed getting the same power.

Merry Lies, geddit? Way to undermine the anonymous ‘stunt girls’ further.

The cultural impact of ‘stunt girls’

By the late 1890s, the ‘stunt girl’ wave of journalism was over. Other women were making their names as serious journalists. But the idea of a quick-witted, fast-talking, risk-taking intrepid girl reporter stuck around. It’s behind Torchy Blane in Smart Blonde (1937), Superman’s Lois Lane (debut 1938) and Hildy Johnson in His Girl Friday (1940).

Bly, and her imitators, had an immediate, observational style that still resonates now.

Footnotes

- Kroeger ↩︎

- Roggencamp, citing Kathleen Cairns, Front Page Women Journalists, 1920-1950 (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2003) ↩︎

- Lutes ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Vorachek ↩︎

- Rogness ↩︎

- Kroeger ↩︎

- Roggencamp ↩︎

- Todd, Journalism History podcast ↩︎

- Nellie Bly, Feb 23 1896 ↩︎

- Lutes ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- see https://undercover.hosting.nyu.edu/s/undercover-reporting/item-set/61 ↩︎

- Lutes ↩︎

- Todd, Smithsonian ↩︎

Sources for Nellie Bly and the ‘stunt girls’

Front page girls: women journalists in American culture and fiction, 1880-1930 by Jean Marie Lutes. (Cornell University Press, 2006)

“How little I cared for fame”: T. Sparrow and Women’s Investigative Journalism at the Fin de Siècle by Laura Vorachek, Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 49, No. 2 (Summer 2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/26166570

Nell Nelson and The Chicago Times “City slave girls” series : Beginning a national crusade for labor reform in the late 1800s, by Eric Liguori, Journal of Management History, Vol 18, No 1. (January 2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17511341211188655

Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters”, by Kim Todd (Harper, 2021)

Stunt Girl Journalism: Eva McDonald Valesh and the Rhetorical Enactment of the Labor Movement by Kate Zittlow Rogness, Minnesota History, Vol. 67, No. 6 (SUMMMER 2021) https://www.jstor.org/stable/48769198

Sympathy and Sensation: Elizabeth Jordan, Lizzie Borden, and the Female Reporter in the Late Nineteenth Century by Karen Roggenkamp, American Literary Realism, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Fall, 2007) https://www.jstor.org/stable/27747271

These Women Reporters Went Undercover to Get the Most Important Scoops of Their Day, by Kim Todd, Smithsonian magazine, November 2016

Todd Podcast: Girl Stunt Reporters, Journalism History podcast interview with Kim Todd, November 2022.

Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception, by Brooke Kroeger (Northwestern University Press, 2012) http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt22727sf.9

Women’s History Month—Undercover Women, by Kim Todd (undated)

Like what we do?

- You can find us on BlueSky and Mastodon, where we post daily about the women that have – and are – making history.

- You can buy us a ko-fi to support the running costs of the server, books and Mags’ caffeine habit.

- Explore our posts tagged women writers to discover other professional women writers.