History is a fragile thing. Writing history is about constructing a narrative based on the evidence we have of the past. It depends on people keeping records and making them available.

‘Who controls the past,’ ran the Party slogan, ‘controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’

George Orwell, Nineteen-Eighty-Four

One reason women’s history exists as a topic within the wider field is how often those records were not kept or were not made available. Writing about women in history is about expanding the evidence base. It’s about broadening the story we tell of ourselves. So it is awful to watch a purge of women from a national history in real time.

Cryptologic: a case study in hiding the past

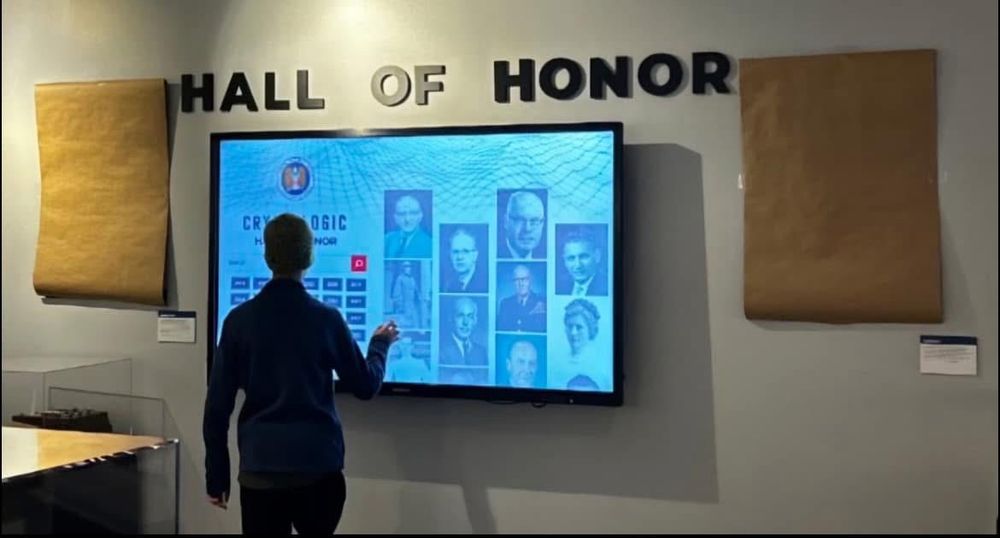

The National Cryptologic Museum in Maryland, USA, is dedicated to “the people who devoted their lives to cryptology and national defense”. Unsurprisingly, there is a strong focus on codebreaking during World War 2 and the National Security Agency (NSA) as it went into the Cold War.

Women codebreakers worked at the NSA. British codebreaker Betty Webb was so good at breaking Japanese codes at Bletchley Park that she was sent to DC to help the US service. The US Marines employed between 400 and 500 Native American men as code talkers. They used codes developed from indigenous languages to transmit tactical information. The people who helped the NSA defeat fascism are highlighted on panels in the museum’s roll of honor display.

Some time between 20 January 2025 and 2 February 2025, someone in the museum took a roll of brown paper and covered up the wall panels.

Gen. Michael Hayden, a former Director of CIA and NSA, noticed and posted about it around 10am on 2 February.[i] By 2pm, the museum was posting about the display decision. Vaguely.

“The National Cryptologic Museum is dedicated to presenting the public with historically accurate exhibits and we have corrected a display mistake.”[ii]

Eric Williams, a retired USAF Intel Analyst, checked the brown paper had come down the next day. [iii]

This shows how fragile the place of women and people of colour is in America’s telling of its history. This was done by a museum that focusses on people’s role in breaking fascism. It’s hard to parse the doublethink required. Some commentators think the brown paper was malicious compliance as it made such a big “look what we can’t show you” statement. The museum reversed its “display mistake” because a powerful (white male) ally called them out publicly. But now time and effort will have to go in repeatedly checking the display board are still there. And how many other erasures will not be reversed because no-one with power calls them out?

Stopping the erasure of people from history

It’s hard to keep track of where history is being erased, covered up or rewritten. There was an image of blank walls at one federal organization which I forgot to bookmark and so have already lost. Just a few examples include:

- Pauli Murray has been removed from the National Parks website..[iv] We’ve used Pauli in the feature image at the top of this post.

- The National Parks also removed all mention of the trans women who led the Stonewall riot.[v]

- The Defense Intelligence Agency removed displays about both women and Black people. In a museum that can only be accessed if you have clearance.[vi]

- Elementary school libraries removing all books about slavery and the civil rights movement.[vii]

As soon as it became apparent what was happening, people set the Internet Archives’ bots trawling all the US government websites so that a record of what was once there is kept. But a museum that’s behind security clearances? Examples like that are much harder to record. It might seem impossible for things to be lost now, but anyone trying to find information out from less than a century ago knows how easy it is for evidence to vanish. History is a fragile thing.

Individual actions – whether that’s using your power as a former director of the NSA or instructing IA to crawl a site – will save a lot of the fragile history that is being so carelessly thrown aside. Future historians will thank every person who saves the past for the future.

[i] Gen M Hayden post of 2 Feb 2025 (BlueSky)

[ii] National Cryptographic Museum vague post of 2 Feb 2025 (Facebook)

[iii] Eric Williams post of 3 Feb 2025 (Bluesky)

[iv] Serqet post on 15 Feb 2025 (Bluesky)

[v] Park Service erases ‘transgender’ on Stonewall website, uses the term ‘LGB’ movement (NPR)

[vi] Intel Agency Confirms It Removed So-Called DEI Items From Its Secured Museum (HuffPo)

[vii] Books mentioning slavery, civil rights removed from shelves at Fort Campbell schools (ClarksvilleNow)