On 21 June 1553, King Edward VI of England and Ireland convinced his noblemen to sign a document agreeing that his cousin Lady Jane Grey would inherit the crown when he died. She lost her head instead.

This month, we look at Lady Jane Grey’s place in history. How and why did she end up as a missing queen?

Lady Jane Grey

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, and that piece of parchment meant Lady Jane Grey was immediately the regnant queen of England and Ireland, ruling the countries in her own right. The English crown immediately goes to the next in the succession. As in, it’s in a blink of an eye. However, they then need to be proclaimed monarch a few days later and crowned some months later again. It’s possible for someone to be proclaimed ruler, and never be crowned and it’s this grey area where Jane – and the earlier Empress Matilda – reside. If you had a ruler with the rulers of England on it (or know the Horrible Histories song), only those that got to actually wear the hollow crown are listed.

And the succession is not automatic. In Tudor times, the current monarch gets to decide who is in and out of the line of succession. Plus, there’s the whole male-preference primogeniture business where sons got to go at the front of the queue even if daughters were born first. And it all needs to have been rubber-stamped by Parliament.

So why had Edward named his cousin Jane rather than his sisters? England in the 1550s was in the midst of a religious reformation. Henry VIII had broken from Rome and theoretically made England a Protestant nation with himself as the Head of the Church. Henry VIII had been desperate for a son: his first-born children who survived infancy were Mary, daughter of Catherine of Aragon, and Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn. Mary was Catholic, Elizabeth was Protestant.

When Edward arrived, son of Jane Seymour, Henry cut his daughters out of his succession, even declaring them illegitimate. Henry eventually put them back in line for the succession but never made them legitimate. Edward was duly crowned and was considerably more fervent in his desire to reform England to Protestantism. But Henry’s rules were still in place: if Edward died without children, then the crown would go to Edward’s half-sister Mary and then through her children. Edward was still a teenager, just fifteen years old, when everyone realized he was dying.

How did Edward make Jane next in line to the throne?

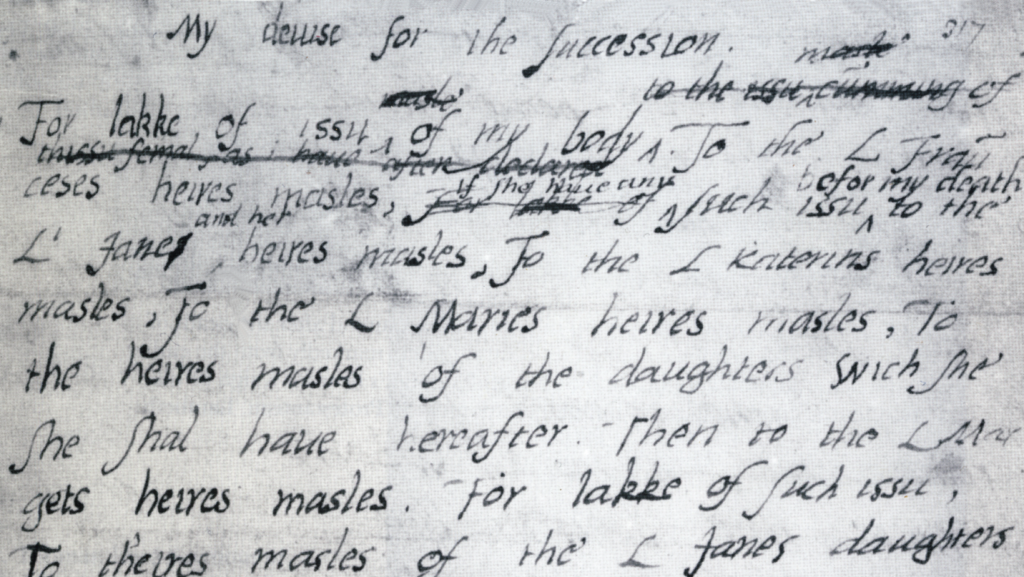

The first devise Edward drew up – a legal document containing his succession – named the sons of his aunt, Lady Frances, as next in line for the throne and excluded both his half-sisters. His aunt only had daughters though. Rather than risk the Catholic Mary gaining the throne and undoing his reforms, Edward crossed out the bit about Lady Frances’ sons. That jumped her eldest daughter, Lady Jane Grey, up the list from fifth in line to first in line.

Jane was a bookish girl, raised around the edges of court. At one point she was being manoeuvred to marry Edward but that fell apart due to a court plot. Jane was also as fervent a protestant as Edward and was eventually married to the son of one his close advisors.

All his ministers and nobles signed the devise agreeing the sixteen-year-old Jane would get the crown next. Yep, they all agreed with the dying king what a great idea it would be, and there was absolutely no self-interest going on at all. Nope. They’d get the bit of paper through Parliament, and it would all be fine.

What hadn’t been properly factored in was Edward’s eldest half-sister Mary. Mary was in her 30s. She had been disowned, then brought back into her father’s favours. When Henry was without a wife, she was the main host at court. She knew how things worked. She’d kept out of Edward’s way. She even avoided a summons to court in his dying days as she’d heard it was a feint to capture her and prevent her attempting a coup. Instead, she fled to the East of England, a stronghold of the Catholic faith, and started building support.

Nine days in July

Edward died on 6 July 1553. His death was kept secret for four days whilst his ministers arranged for Jane to be safely moved to the Tower of London, where monarchs lived between their ascension and their coronation. They also apparently broke the news to Jane, who had been unaware her father-in-law had been manoeuvring her into place. Jane was formally proclaimed regnant queen on 10 July 1553. She started making plans to pass an act of parliament so her husband could be king. She started signing things as “Jayne the Quene”.

But the document making Edward’s wishes the law had not been totally signed off.

By 19 July Jane had been deposed by those ministers after they saw the way the wind was blowing from the east. By the start of August Mary was riding into London with her half-sister Elizabeth at her side and 800 nobles and gentlemen behind her.

Why Lady Jane lost her head

Mary put Jane on trial for treason. Her signing documents as “Jane the Quene” was used to show she had claimed the throne when she had no right to it. She was found guilty in November 1553. The penalty for treason for noblewomen was death by fire or axe. Jane’s father-in-law was executed straight after the trial, but Jane and her husband weren’t.

Perhaps Mary might have left Jane and her husband mouldering in the Tower. Perhaps she might have had sympathy for a bookish teenage girl, newly married, who had been made queen without warning. Perhaps she had seen enough of her father’s behaviour to know how court intrigues could use and abuse people for power.

The problem was those advisors and nobles. Again. Jane’s father got involved in a rebellion to prevent Mary marrying the King of Spain – a foreigner! – and switching England back to Catholicism. The failed rebellion hadn’t even planned to put Jane back on the throne: it had favoured Elizabeth. Mary had no choice. Her cousin Jane’s sentence had to be carried out to remove a threat to her own power. She gave Jane the choice of converting to Catholicism to save her life. Jane refused and was beheaded on 12 February 1554.

After her death, Jane’s story was used in protestant propaganda, and she was portrayed as an innocent martyr – a victim of “Bloody Mary”. Her story has been heavily romanticised, and quite a few artists have got a bit overwrought painting her execution. It’s hard to tell how true the story of her innocence is: the Tudor equivalent of shredding the evidence happened a lot in those months between her proclamation and her execution. What with the whole penalty for treason being having your head removed.

Both Jane’s successors – Mary I and Elizabeth I – wanted, gained, and held power for themselves. Lady Jane Grey had the crown thrust upon her by others. The day in June when Edward crossed out “sons” on a piece of paper is the day Jane’s fate was unknowingly sealed.

Want to dig into Lady Jane’s story more? Here’s some sources.

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/15/teen-queen

- https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/history-and-stories/lady-jane-grey/#gs.06046t

- https://www.royal.uk/lady-jane-grey

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Lady-Jane-Grey/

- https://www.npg.org.uk/support/individual/face-to-face/lady-jane-grey

Like what we do?

You can also discover some of our other posts about events in June.

You can find us on BlueSky and Mastodon, where we post daily about the women that have – and are – making history.

You can buy us a ko-fi to support the running costs of the server, books and Mags’ caffeine habit.