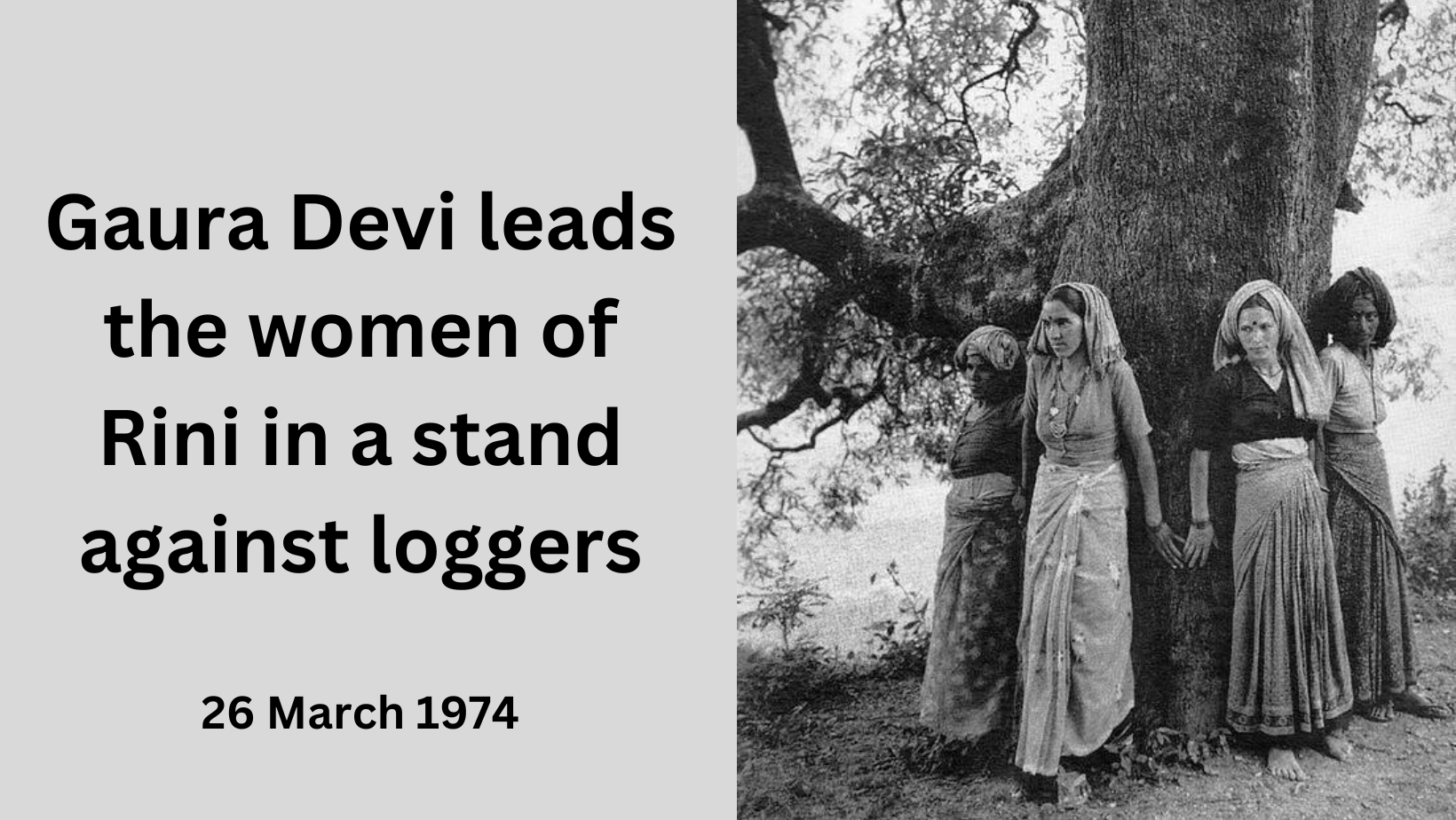

In March 1974, a group of women in a Himalayan village stood in front of armed men who come to chop down the forest. Led by Gaura Devi, the women encircled the trees.

This month, we look at some of the women fighting deforestation.

Continue reading “Gaura Devi and other women fighting deforestation”