It’s over 50 years since the first standalone newsstand edition of Gloria Steinem’s Ms. Magazine was published (1 July 1972). And yet women still have conversations about boring life admin in which they must answer the question “Miss or Mrs?” with “It’s Ms, actually.” So here’s a brief history of the title, for when someone assumes you’re using it to indicate you’re divorced (yes, that really still happens).

Continue reading “A brief history of Ms.”Charlotte E Ray and 143 years of progress

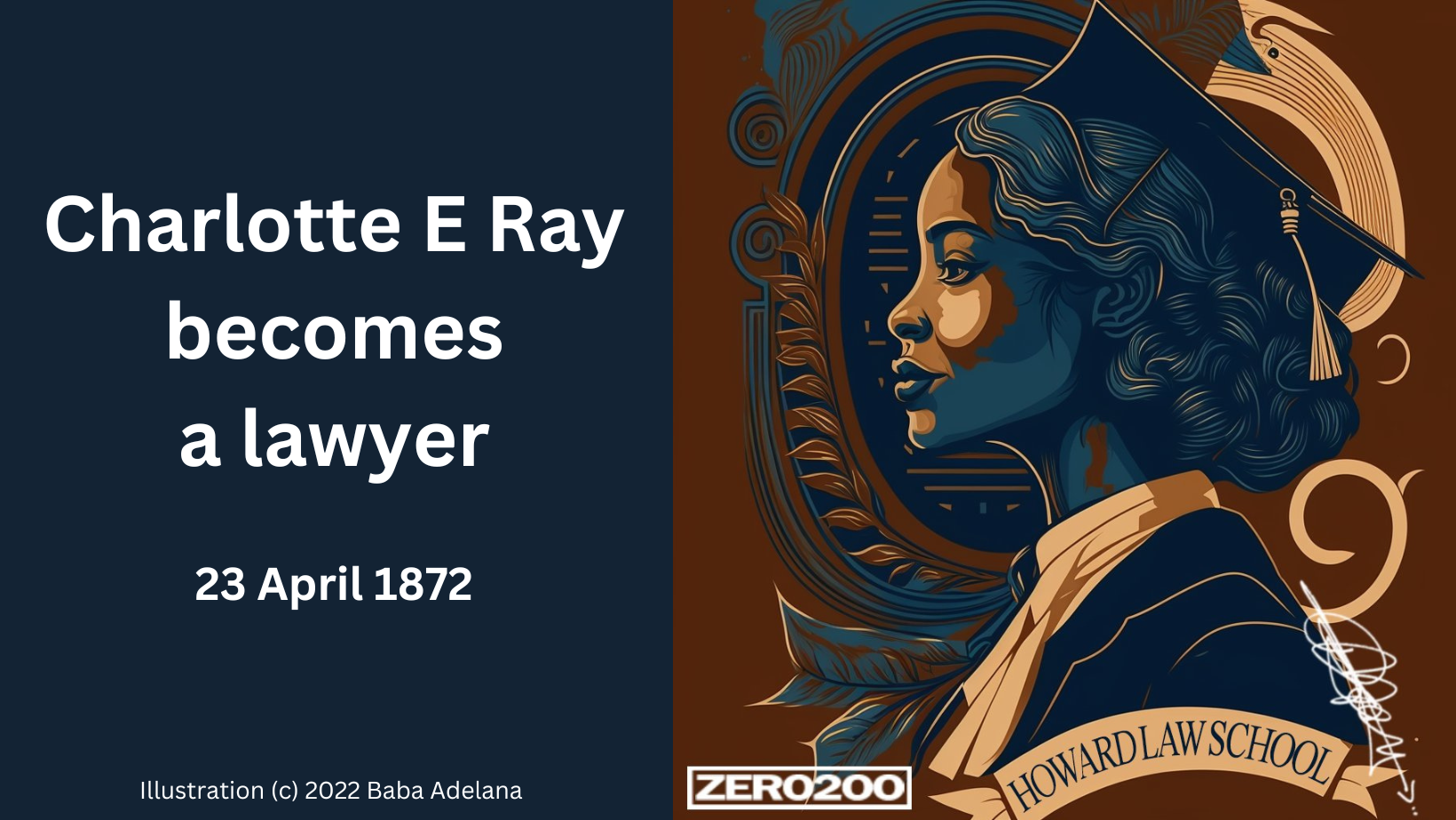

The first African-American woman to be Attorney General of the USA, Loretta Lynch, was appointed on 23 April 2015 in Washington DC. The very same day, 143 years earlier in 1872, Charlotte E Ray became the first African-American woman admitted to practice law in the USA.

Sometimes history throws up these little co-incidences. This one gives us the opportunity to look at two very different law careers available to a Black woman in the USA.

Continue reading “Charlotte E Ray and 143 years of progress”Eight famous women singers

On 15 May 1946, Camilla Williams made her debut as Cio-Cio San in the New York City Opera’s production of ‘Madame Butterfly’. She was the first black woman to sign a contract with a major US opera company. This month, we take a quick look at eight of the most iconic female singers in opera history.

First up, it’s worth noting that opera was hugely popular from the 1700s to the 1960s. These famous women singers were as popular in their time as Beyonce or Lizzo now. It’s also worth noting that opera singers were seen as disreputable and scandalous in the 1700s, and this social attitude continued into the 1800s. As ever, powerful, financially independent women using their voices had to be cast out in some way.

This month we’re focussing on female popular singers from the 1830 onwards. Maybe we’ll visit the Covent Garden of the 1700s another time…

Continue reading “Eight famous women singers”Valentina Tereshkova reaches orbit: 16 June 1963

On 16 June 1963, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space, orbiting the Earth 48 times in Vostok 6. With her flight, she clocked up more hours in space than all the preceding American manned missions combined. She remained the only woman to have flown in space for 19 years and she remains the only woman to have completed a solo space mission.

Continue reading “Valentina Tereshkova reaches orbit: 16 June 1963”Alison Hargreaves summits Everest: 13 May 1995

On 13 May 1995, professional British mountaineer Alison Hargreaves reached the summit of mount Everest in the Himalayas. She was the first woman – and only the second person – to summit without either support from a Sherpa team or supplementary oxygen.

Hargreaves had set her ambition out clearly and shown she was going for it: she would become the first woman to climb Everest, K2 and Kanchenjunga – the three highest mountains in the world – without oxygen.

Continue reading “Alison Hargreaves summits Everest: 13 May 1995”Violeta Chamorro sworn in: 25 April 1990

On 25 April 1990, Violeta Chamorro was sworn in as President of Nicaragua. She was the first female President in the Americas to have come to power under a free election.

Chamorro led the country for seven years, overseeing the end of the civil war between the Sandinistas (Marxist revolutionary government forces) and the Contras (US-backed counter-revolutionary forces).

Continue reading “Violeta Chamorro sworn in: 25 April 1990”Greenham Women: 22 March 1982

On 22 March 1982, around 250 women block access to the airbase at Greenham Common in the UK. It is the first time the women’s peace camp has put non-violence to the test on a large scale, and 34 women are arrested. By the end of 1982, 30,000 women would arrive for the ’embrace the base’ protest. By 1983, over 100 similar peace camps are set up near nuclear sites around the world.

Continue reading “Greenham Women: 22 March 1982”Lorraine Hansberry: 11 March 1959

On 11 March 1959, Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun debuts on Broadway in New York. She is the first female African-American playwright to be staged there.

Continue reading “Lorraine Hansberry: 11 March 1959”