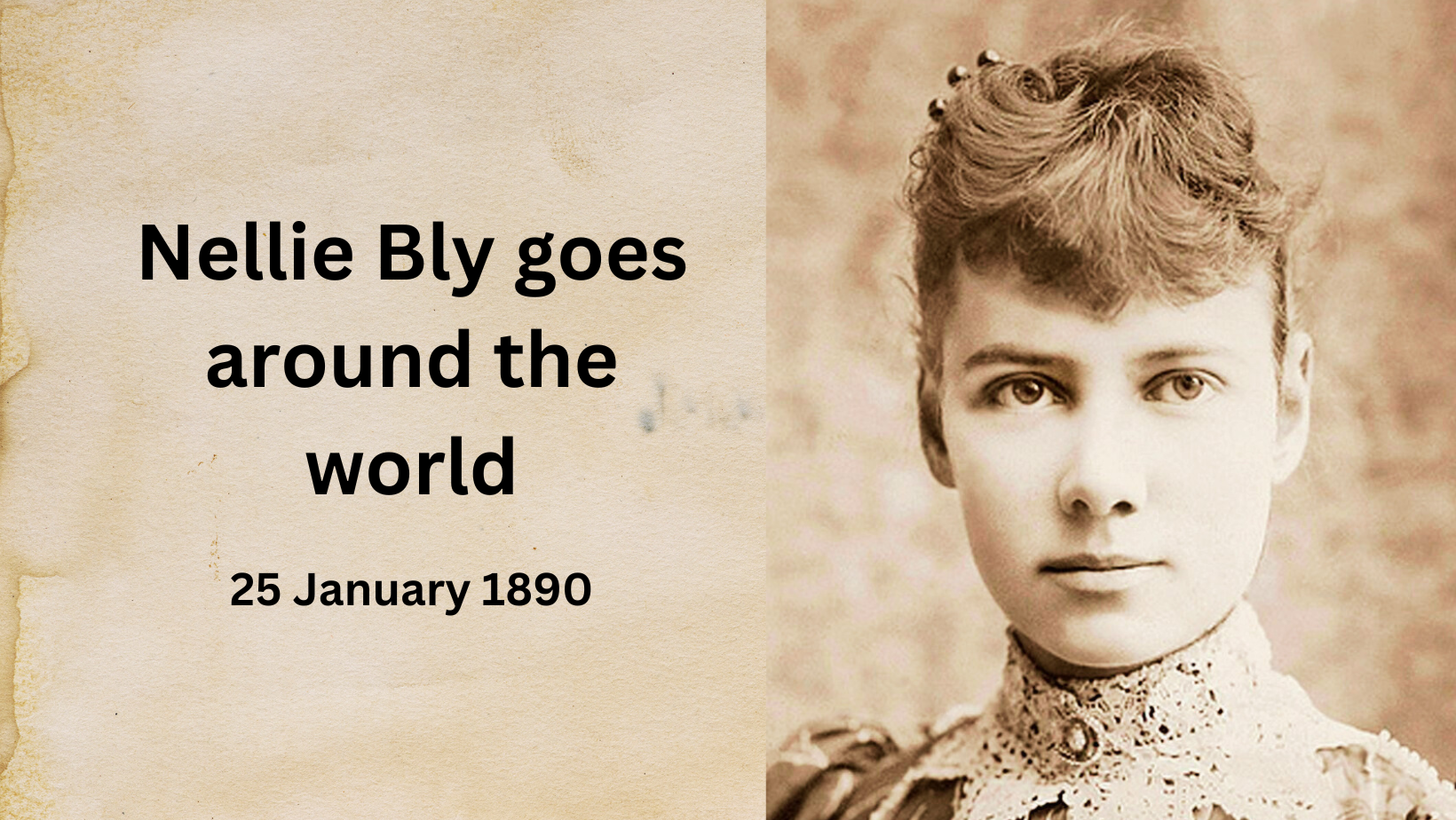

On 25 January 1890, American journalist Nellie Bly stepped off a train in New York and into a huge crowd that was waiting for her. She had just become the first person to travel around the world in less than eighty days. Not only had she done it, she had beaten her rival, Elizabeth Bisland, by four days.

The 1890 race around the world reveals that Bly, perhaps the most famous newswoman then writing, was not unique. From 1887 through to the middle of the 1890s, the ‘stunt girls’ made front page news. They wrote it, and they became it.

So in this post we’re looking at the rise and fall of stunt journalism, and the women involved in it.

Continue reading “Nellie Bly and the incognito ‘stunt girl’ reporters”